Ageing has its hills and ravines: there’s a slowing down that can be relaxing after the intensity of postmodern life, some of the mysteries of living become just a little clearer with the wisdom of hindsight; the valleys include the persistent and pesky aches and pains from past injuries that were easy to forget when younger and stronger, failing vision, a few extra (and unneeded kilos), and most difficult of all the loss of old friends.

Twenty-nine years ago I left beautiful Petaluma, California, and the Bay Area to head off to the jungles of what was then called Irian Jaya and is now known as Papua and West Papua. I wasn’t expecting to stay more than  the year contract that I had in my baggage as I arrived in the little town of Timika where the mining company that I was going to be working for had their airport. I didn’t know much about what to expect other than what was offered in a brief orientation at the mining company’s headquarters in New Orleans. No friends, a new school, a new language to learn, leaving family and friends behind. It was a bit daunting for someone who loves routine to keep some of the demons of life away.

the year contract that I had in my baggage as I arrived in the little town of Timika where the mining company that I was going to be working for had their airport. I didn’t know much about what to expect other than what was offered in a brief orientation at the mining company’s headquarters in New Orleans. No friends, a new school, a new language to learn, leaving family and friends behind. It was a bit daunting for someone who loves routine to keep some of the demons of life away.

Not long after I arrived, I started heading out on the weekends into the villages of the local ethnic groups that lived just outside of the fenced mining community that I called home. And it was not too much longer before I came across the man who was to become one of my best friends during the nine years that I spent in Irian Jaya; that friendship continued on over the years only ending yesterday when I heard that he had passed on.

Hasan Merdjanic and I were in a sense an odd couple; he was a capitalist from the former Yugoslavia; I was a  socialist from Chicago. He was a master mechanic; I was a second grade teacher. He was outgoing and cheerful; I was introverted and brooding. But our love of Indonesia, and especially Irian Jaya was the foundation on which we built our long friendship.

socialist from Chicago. He was a master mechanic; I was a second grade teacher. He was outgoing and cheerful; I was introverted and brooding. But our love of Indonesia, and especially Irian Jaya was the foundation on which we built our long friendship.

We were both single at the time, living in the BQ buildings just across the river from the Sports Hall. Hasan introduced himself one afternoon in the F-Barracks dining area. He had heard that I was interested in the local  people and their cultures. Over dinner, we shared some basic background information and when he heard that I had a Ph.D. In anthropology, he gave me the nickname of drbruce. I’ve kept that nickname since then. And, he told me about his project – the Timika Yacht and Swim Club. This was a place for the three groups of people living and working for the mining company – expats, locals and Indonesians from other islands – to get together in their free time and recreate together and get to know each other and hopefully break down some of the boundaries and stereotypes that social groups tend to hold dear. I was impressed with the beauty, boldness and difficulty of Hasan’s vision. Still, it took a few months before I was ready to cough up the $100 membership fee.

people and their cultures. Over dinner, we shared some basic background information and when he heard that I had a Ph.D. In anthropology, he gave me the nickname of drbruce. I’ve kept that nickname since then. And, he told me about his project – the Timika Yacht and Swim Club. This was a place for the three groups of people living and working for the mining company – expats, locals and Indonesians from other islands – to get together in their free time and recreate together and get to know each other and hopefully break down some of the boundaries and stereotypes that social groups tend to hold dear. I was impressed with the beauty, boldness and difficulty of Hasan’s vision. Still, it took a few months before I was ready to cough up the $100 membership fee.

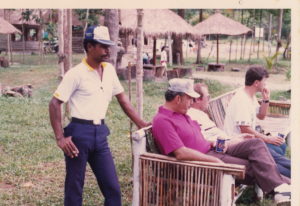

We started our friendship having a few beers in Hasan’s BQ or mine talking about what he was doing. Eventually he dragged me down to Timika and the Kaoga River where the Yacht Club was located. At the time it was just an office building and a few bbq areas. But people would come there on the weekend on cook, swim in the icy river and just hang out. A few small stalls selling food opened up on the road outside the club. Hasan’s dream was becoming a reality.

We started our friendship having a few beers in Hasan’s BQ or mine talking about what he was doing. Eventually he dragged me down to Timika and the Kaoga River where the Yacht Club was located. At the time it was just an office building and a few bbq areas. But people would come there on the weekend on cook, swim in the icy river and just hang out. A few small stalls selling food opened up on the road outside the club. Hasan’s dream was becoming a reality.

After my first visit and my introduction to the small Amungme man who was the landlord for the Yacht Club, I was hooked on Hasan’s vision. Anytime that Hasan was going down to work at the Club, I hitched a ride along with him and took part in what turned out to be years of construction work as the Yacht Club went from the office building to include a two-story building with rooms for rent on the second floor and then the so-called Animal House for guys who wanted to come down and party away from the general crowd who came in on the weekends, more bbq’s, a building with toilets and showers, a kids’ playground, a restaurant, and finally a little golf course hacked out of the jungle where the idea was to hit a ball and not lose it.

My favorite times were the early days of construction when we would put up a tarp to cover us and sit around a campfire to keep the mossies away and drink and tell stories through the night. Hasan would bring his music  box down and we had some of the classic 90s music to provide a soundtrack for our campfire stories. During the day, we’d help with construction; it was hot, dirty work but Hasan had this unique ability to draw all sorts of expat guys down to help out. He was the ringmaster of our weekend circuses.

box down and we had some of the classic 90s music to provide a soundtrack for our campfire stories. During the day, we’d help with construction; it was hot, dirty work but Hasan had this unique ability to draw all sorts of expat guys down to help out. He was the ringmaster of our weekend circuses.

Hasan had that ability to sell people on his vision: guys would work for free, the mining company would donate some of the building supplies that we needed, we had a local manager, a genial Javanese guy who ended up in Timika as part of the Indonesian government’s relocation plan. Hasan brought all of us in together. We had a little group of my teacher friends who would come down occasionally on the weekends to swim, eat and play.

At some point Hasan made me a vice-president of the Yacht Club in charge of art and culture. I would come  down and scour Timika looking for Asmat carvings that we could sell at the Club. Sometimes I would find one or two tucked away in some small shop; once I came across a darkened little house with some statues outside. Peering inside a small cobwebbed window, I caught a glimpse of dozens of carvings piled up randomly on the floor and leaning against the walls of the room.

down and scour Timika looking for Asmat carvings that we could sell at the Club. Sometimes I would find one or two tucked away in some small shop; once I came across a darkened little house with some statues outside. Peering inside a small cobwebbed window, I caught a glimpse of dozens of carvings piled up randomly on the floor and leaning against the walls of the room.

It took a while to track down the owner of the carvings as I went from house to house asking who lived in the statue house. Eventually, we hooked up and made our way back to the treasure trove. I tried bargaining for individual statues, but the prices were more than I wanted to pay. As a final tactic, I offered to buy all of his carvings for one price. Deal. But, I didn’t have enough money so I raced back down the dirt road that connected Timika to the Yacht Club leaving a trail of billowing dust behind me. As I screeched to a stop, Hasan popped out of the office and, giving me a dubious look asked, “What have you done Dr.Bruce?” I told him I had 73 carvings but no money. He pulled out a roll of notes, counted them out, took my wallet and emptied it and gave me his favorite saying, “Make yourself useful and do something.”

I was reliving this story just yesterday as I was photographing and cataloging the remaining statues that I brought back with me to Bali when I left Irian Jaya. And then one of those moments of synchronicity; I took a break to check my email and saw the notice of Hasan’s passing.

It was only a few months ago that we sat along the Esplanade in Cairns trying to stay out of the morning rain while we discussed our various illnesses and the ravages of ageing. I showed him the scars on my leg from the tropical ulcers I picked up on my most recent trip to Papua. He showed me his heart surgery scars. But, as always, he was upbeat, but realistic. We made some plans to meet again, either in Bali when he felt better or back in Cairns if I did another run on the cruise ship that he had talked me into working on as something to “make myself useful.”

I didn’t suspect that that would be the last time that I would get the pleasure of spending time with my old friend. Probably that was for the best, I’m not known for being good at sentimentality. But, I would have liked to have told him how much his friendship over the years meant to me, although knowing Hasan, I pretty much guess that he was clued into that as he was clued into so many things in this life of adventure and mystery. Rest in Peace Buddy. Miss you already.

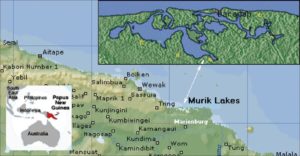

They live in five main villages in an area of mangrove lakes, swamps and sandy beaches. This area makes up the largest mangrove ecology in PNG.

They live in five main villages in an area of mangrove lakes, swamps and sandy beaches. This area makes up the largest mangrove ecology in PNG. marriage patterns.

marriage patterns.

While at one time the ideal was to have houses arranged by descent groups, that pattern is less likely to be followed these days because of the frequent flooding of the land. Extended families usually live together until it gets too crowded

While at one time the ideal was to have houses arranged by descent groups, that pattern is less likely to be followed these days because of the frequent flooding of the land. Extended families usually live together until it gets too crowded me so pervasive in PNG and lacking land to grow cash-crops and trees to sell to the foreign concessions, the Murik are dependent on the occasional sales of carvings and baskets, as well as remittances from family members who have moved to the cities to engage in paid labor. I was told in Mendam (as I was in all of the villages that I visited) that they welcomed tourism because it provided a cash income and encouraged the younger members of the community to keep up with the traditional culture.

me so pervasive in PNG and lacking land to grow cash-crops and trees to sell to the foreign concessions, the Murik are dependent on the occasional sales of carvings and baskets, as well as remittances from family members who have moved to the cities to engage in paid labor. I was told in Mendam (as I was in all of the villages that I visited) that they welcomed tourism because it provided a cash income and encouraged the younger members of the community to keep up with the traditional culture.

hnic groups in the Sepik River area, the Murik have a distinctive style of carving. Masks tend to display a stylized oblong form. A carving school for youths to keep the art alive and for people who felt there was nothing in the modern world for them was started by a well-known former politician who owns a large resort in Madang and who is frequently on the Sepik River with his luxury yacht filled with tourists who want to experience the cultures of the Sepik River.

hnic groups in the Sepik River area, the Murik have a distinctive style of carving. Masks tend to display a stylized oblong form. A carving school for youths to keep the art alive and for people who felt there was nothing in the modern world for them was started by a well-known former politician who owns a large resort in Madang and who is frequently on the Sepik River with his luxury yacht filled with tourists who want to experience the cultures of the Sepik River. The Murik Lakes Resettlement Project (MLRP) was started in 2003 but failed. Local initiatives followed, and a new village was built after the 2011 tsunami. Temporary solutions have yet to lead to permanent ones. This is the challenge for the Murik and other coastal dwelling people today.

The Murik Lakes Resettlement Project (MLRP) was started in 2003 but failed. Local initiatives followed, and a new village was built after the 2011 tsunami. Temporary solutions have yet to lead to permanent ones. This is the challenge for the Murik and other coastal dwelling people today. t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung.

t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung. The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach.

The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach. This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two.

This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two. Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post.

Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post. know if she would like them as gifts, but she stuffs things down inside and says, “I have a surprise inside my bilum, Grandpa, do you know what it is?” And then there are the masks that I brought back and have hanging on the wall and the sacred flutes that Zoey likes me to play. So PNG is in my awareness constantly.

know if she would like them as gifts, but she stuffs things down inside and says, “I have a surprise inside my bilum, Grandpa, do you know what it is?” And then there are the masks that I brought back and have hanging on the wall and the sacred flutes that Zoey likes me to play. So PNG is in my awareness constantly. I just happened to find an anthropologist who had been through this experience years before me; another American living over in this corner of the world who had worked on the same cruise ship that I have just finished traveling on. She wasn’t an academic anthropologist, she called herself (at least on her blog) as an applied anthropologist, and it turned out she had a blog where she wrote about her life in PNG.

I just happened to find an anthropologist who had been through this experience years before me; another American living over in this corner of the world who had worked on the same cruise ship that I have just finished traveling on. She wasn’t an academic anthropologist, she called herself (at least on her blog) as an applied anthropologist, and it turned out she had a blog where she wrote about her life in PNG.

el in the south. Sakti, according to the Babad Buleleng, traced his descent back to the fabled Majapahit Empire in Java. Sakti’s descendents ruled Buleleng until the late 18th century when the kingdom was taken over by Karangasem. By 1840 Buleleng was ruled by Anak Agung Ngurah Made Karangasem along with the powerful prime minister I Gusti Ketut Jelantik. Under his charismatic leadership, Buleleng became one of the most powerful kingdoms on the island. But, the Dutch, who had paid little substantial attention to Bali up until the 18th century because of its lack of spices, became interested in securing treaties with the Balinese kings in order to establish themselves on the island so that any British ambitions for Bali would be abandoned. By 1845 the Dutch had successfully established treaties with most of the Balinese kingdoms.

el in the south. Sakti, according to the Babad Buleleng, traced his descent back to the fabled Majapahit Empire in Java. Sakti’s descendents ruled Buleleng until the late 18th century when the kingdom was taken over by Karangasem. By 1840 Buleleng was ruled by Anak Agung Ngurah Made Karangasem along with the powerful prime minister I Gusti Ketut Jelantik. Under his charismatic leadership, Buleleng became one of the most powerful kingdoms on the island. But, the Dutch, who had paid little substantial attention to Bali up until the 18th century because of its lack of spices, became interested in securing treaties with the Balinese kings in order to establish themselves on the island so that any British ambitions for Bali would be abandoned. By 1845 the Dutch had successfully established treaties with most of the Balinese kingdoms. this trip, I was playing with the concept of consciousness (not in the sense of how some of the new arrivals to Bali use it, such as in “Oh ya, I’m a conscious person,” but in the scientific sense of the word.) Consciousness is a favorite concept to think about just because of the act of perceiving and thinking about the beauty found around Bali on the way up to Ubud from Singaraja. The sense of being in the world can be really startling when immersed in the lushness of a tropical island.

this trip, I was playing with the concept of consciousness (not in the sense of how some of the new arrivals to Bali use it, such as in “Oh ya, I’m a conscious person,” but in the scientific sense of the word.) Consciousness is a favorite concept to think about just because of the act of perceiving and thinking about the beauty found around Bali on the way up to Ubud from Singaraja. The sense of being in the world can be really startling when immersed in the lushness of a tropical island. nding a pleasant afternoon catching up with an old American friend and his Balinese wife. And, as usual, I did my shopping tour through town to get a few things for Zoey, Zander and Su. I made my obligatory stop at Ganesha Books to get Zoey a few books, and I succumbed to the desire to spend a quiet evening in my room by ordering a pizza from a local restaurant.

nding a pleasant afternoon catching up with an old American friend and his Balinese wife. And, as usual, I did my shopping tour through town to get a few things for Zoey, Zander and Su. I made my obligatory stop at Ganesha Books to get Zoey a few books, and I succumbed to the desire to spend a quiet evening in my room by ordering a pizza from a local restaurant.