As Zoey and I return home from our morning walk around the city, she’s drawn in to a number of rapid fire conversations with her kampung friends (she spends more time out playing everyday with friends now; Grandpa time often takes second place to playtime in the neighborhood). She’s smart and sassy, so much like her mother, grandmother and youngest aunt; my oldest daughter and youngest son take more after me – thoughtful and somewhat reticent in dealing with others. Zoey gets into a verbal taunt with a friend who is twice her age, and she holds her ground. She switches off effortlessly into English with me when she asks if it’s ok to play with her friends rather than come upstairs to her room to play with me. She grabs some snacks that she’s bought at the mini-market, gives one to a friend and off she goes.

A group of these little kampung urchins gather round to watch a neighbor who’s crafting a new outrigger boat. The kids still learn about traditional ways by watching the adults; none of the adults mind the audience unless they get in the way of the work. It’s a scene that’s gone on in this kampung for hundreds of years. But one of them pulls out a tablet and snaps a photo of his uncle a t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung.

t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung.

I’ve been trying to get a grasp on the issue of modernity versus tradition (if it’s really a binary thing, and it certainly doesn’t appear to be) in PNG, but it dawns on me that very similar processes are at work here. Maybe that’s what has thrown me off integrating my most recent trip to PNG into my somewhat idiosyncratic world view. I was having dinner with a few guests on the cruise ship and one of them remarked that my wife sounded very traditional.

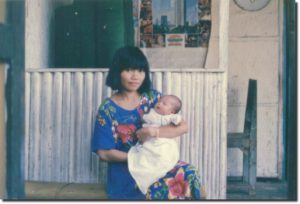

That remark just came to mind today while I was cleaning the house and moving some of my wife’s traditional medicines out of the way.  The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach.

The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach.

Tradition and modernity are all around me, but I miss a lot of it because in so many ways, I really have (as I’ve been accused of by several former anthropologist colleagues) gone native for the most part and so what seems strange and exotic to Western outsiders is just another regular, non-remarkable event for me that I gloss over like so many of the ceremonies and colorful cultural artifacts that bring millions of visitors to this tiny island every year.

And then there’s tourism that gets thrown in this mix. I came here as a tourist as all of the foreigners who live here did, but over the years I’ve grown to view tourism mostly through its negative aspects. But tourism is one of the economic and cultural forces that I’ve come to reconsider after my month on the Sepik River. And accordingly, I need to do so here as well. Lots of things to reconsider; that in itself is actually refreshing as the events of the last six months have shaken me out of my tropical lull and started me on taking a look at the local and the foreign in some new ways.

The movement from tradition to modernity doesn’t have a simple linear trajectory; it twists and turns, advances and retreats. Some aspects of modernity are adopted and modified to fit into the regular flow of life; technology seems to be the easiest path to be adapted, ideology the hardest. And there’s the sticky problem of the definition of both modernity and tradition.  This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two.

This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two.

In both Indonesia and Papua New Guinea there are serious existential concerns about the viability of traditional culture under the onslaught of 21st century modernity and globalization. However, they are opposite sides of the same coin;  Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post.

Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post.