I’m working on a new video creation project. This is my beta version. I have some other elements that I’ll be adding to this as I get some new tech tools.

I’m working on a new video creation project. This is my beta version. I have some other elements that I’ll be adding to this as I get some new tech tools.

As Zoey and I return home from our morning walk around the city, she’s drawn in to a number of rapid fire conversations with her kampung friends (she spends more time out playing everyday with friends now; Grandpa time often takes second place to playtime in the neighborhood). She’s smart and sassy, so much like her mother, grandmother and youngest aunt; my oldest daughter and youngest son take more after me – thoughtful and somewhat reticent in dealing with others. Zoey gets into a verbal taunt with a friend who is twice her age, and she holds her ground. She switches off effortlessly into English with me when she asks if it’s ok to play with her friends rather than come upstairs to her room to play with me. She grabs some snacks that she’s bought at the mini-market, gives one to a friend and off she goes.

A group of these little kampung urchins gather round to watch a neighbor who’s crafting a new outrigger boat. The kids still learn about traditional ways by watching the adults; none of the adults mind the audience unless they get in the way of the work. It’s a scene that’s gone on in this kampung for hundreds of years. But one of them pulls out a tablet and snaps a photo of his uncle a t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung.

t work, modernity is never far away or totally separated from the traditional life. The kids blend them together without a thought. Their toys include store-bought dolls and laser guns, castoff plastic plates from a recent ceremony and some oddly shaped pebbles that have washed up from the sea in a recent storm. This kind of childhood is far from my own Chicago child life: we rarely interacted with adults, dads were at some sort of work that we only vaguely understood and moms were at home cooking and cleaning. Here it’s like Tom Sawyer and Kim all rolled into one, set against the beautiful Bali Sea in a somewhat seedy fishing kampung.

I’ve been trying to get a grasp on the issue of modernity versus tradition (if it’s really a binary thing, and it certainly doesn’t appear to be) in PNG, but it dawns on me that very similar processes are at work here. Maybe that’s what has thrown me off integrating my most recent trip to PNG into my somewhat idiosyncratic world view. I was having dinner with a few guests on the cruise ship and one of them remarked that my wife sounded very traditional.

That remark just came to mind today while I was cleaning the house and moving some of my wife’s traditional medicines out of the way.  The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach.

The smell of jajan (a wonderful variety of baked goods) rises up to my room from my wife’s kitchen. She’s cooking for the 40-day ceremony for my new grandson. She still makes everything from scratch even though she could more easily buy the things she cooks in a bakery or supermarket. My wife is about as traditional as you can get here, but the tablet that she uses for her regular Facebook postings is never far from reach.

Tradition and modernity are all around me, but I miss a lot of it because in so many ways, I really have (as I’ve been accused of by several former anthropologist colleagues) gone native for the most part and so what seems strange and exotic to Western outsiders is just another regular, non-remarkable event for me that I gloss over like so many of the ceremonies and colorful cultural artifacts that bring millions of visitors to this tiny island every year.

And then there’s tourism that gets thrown in this mix. I came here as a tourist as all of the foreigners who live here did, but over the years I’ve grown to view tourism mostly through its negative aspects. But tourism is one of the economic and cultural forces that I’ve come to reconsider after my month on the Sepik River. And accordingly, I need to do so here as well. Lots of things to reconsider; that in itself is actually refreshing as the events of the last six months have shaken me out of my tropical lull and started me on taking a look at the local and the foreign in some new ways.

The movement from tradition to modernity doesn’t have a simple linear trajectory; it twists and turns, advances and retreats. Some aspects of modernity are adopted and modified to fit into the regular flow of life; technology seems to be the easiest path to be adapted, ideology the hardest. And there’s the sticky problem of the definition of both modernity and tradition.  This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two.

This is a current issue in many of the places that I’ve visited in PNG. What’s tradition, what’s custom, what’s good tradition, what’s bad, what’s the difference between tradition and custom. One example: are young ladies in the Trobriand following tradition when they dance topless in front of camera-clicking (and cash-paying) tourists? And if it’s tradition, is it good tradition or bad tradition. And then there’s land issues. Here the issue revolves less around land problems (a common point of contention in PNG) and more around how cultural actions are played out whether it’s in death rituals, religious rituals or the political translation and mobilization of the two.

In both Indonesia and Papua New Guinea there are serious existential concerns about the viability of traditional culture under the onslaught of 21st century modernity and globalization. However, they are opposite sides of the same coin;  Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post.

Bali is concerned with too much tourism, Papua New Guinea with too little. Finding a balance seems to be the commonsense solution to Bali’s problem, although the eyes of the powers that control such things here seem to be blinded by the color of money. It’s always the more the better. But this issue in Bali has been discussed since colonial days, and with no solution in sight, it’s easy enough to take the cynical view that nothing will change until the whole fragile system collapses under its own weight. For PNG, well that’s something for another post.

Note: Back on the old blog before I lost my domain name, I had a history of Kampung Bugis that I translated from the Indonesian. This document was a senior thesis written by an Indonesian student. It was an interesting history, and unfortunately I’ve misplaced most of the translation except for this section, I’m posting this here with the hope that I will come across the rest of the translation in the future.

Last post on the Bugis, I wrote that I would add some information about the culture of the Bugis who arrived in Bali. This post summarizes the information in from the first section of Chapter 2 of the Migration and the Role of the Bugis in Kampung Bugis Buleleng 1815-1946 by I Nyoman Mardika.

According to Raden Sasrawidjaja who wrote about the Bugis in Kampung Bugis in 1871 when he visited there, the houses of the Bugis who came to Bali had three parts: an upper house under the roof called the Rakkaang where grain, other food supplies and family heirlooms were stored, unmarried girls from the nobility also lived in this section of the house; the second part of the house, the Alebola, consisted of rooms that were used for living, such as bedrooms, a kitchen, a dining room and a receiving room; the third part, the Awasai, was used for livestock, farming gear or fishing gear.

The original geographic boundaries of Kampung Bugis were unclear because there were no firm agreements on borders at this time, but after Indonesia won independence the boundaries of Kampung Bugis were the Java Sea to the north, Tukad Buleleng to the east, Kampung Anyar to the west and Banjar Bali to the south. The population of Kampung Bugis in 1823 was estimated to be around 2,000 residents. The current population is around 3,300.

Kampung Bugis was ideally located for the Bugis people because it is located along the beach close to the center of the town of Singaraja. It is also adjacent to to the customs port of Buleleng. Because this customs port was busy and visited regularly by ships, it was an ideal location for the Bugis who were skilled in trading activities. Also, due to Kampung Bugis’ relatively small, narrow boundaries and sandy soil, farming was not an option as an economic activity. So, the Bugis traded as their main means of livelihood with fishing as a secondary source of income or food. The writer notes that the Bugis are known for their trading ability because of their tradition of sailing and dominating inter-island trade prior to the Dutch intrusion into the islands.

In order to be able to understand the history of the Bugis people in Kampung Bugis, it is necessary to view the kampung and the people in the context of north Bali, or Buleleng. The city of Singaraja was founded in 1604 by I Gusti Panji Sakti who came to the north from the kingdom of Gelg el in the south. Sakti, according to the Babad Buleleng, traced his descent back to the fabled Majapahit Empire in Java. Sakti’s descendents ruled Buleleng until the late 18th century when the kingdom was taken over by Karangasem. By 1840 Buleleng was ruled by Anak Agung Ngurah Made Karangasem along with the powerful prime minister I Gusti Ketut Jelantik. Under his charismatic leadership, Buleleng became one of the most powerful kingdoms on the island. But, the Dutch, who had paid little substantial attention to Bali up until the 18th century because of its lack of spices, became interested in securing treaties with the Balinese kings in order to establish themselves on the island so that any British ambitions for Bali would be abandoned. By 1845 the Dutch had successfully established treaties with most of the Balinese kingdoms.

el in the south. Sakti, according to the Babad Buleleng, traced his descent back to the fabled Majapahit Empire in Java. Sakti’s descendents ruled Buleleng until the late 18th century when the kingdom was taken over by Karangasem. By 1840 Buleleng was ruled by Anak Agung Ngurah Made Karangasem along with the powerful prime minister I Gusti Ketut Jelantik. Under his charismatic leadership, Buleleng became one of the most powerful kingdoms on the island. But, the Dutch, who had paid little substantial attention to Bali up until the 18th century because of its lack of spices, became interested in securing treaties with the Balinese kings in order to establish themselves on the island so that any British ambitions for Bali would be abandoned. By 1845 the Dutch had successfully established treaties with most of the Balinese kingdoms.

Next post: The Dutch Capture of Buleleng

Singaraja is the capital of the regency of Buleleng, which covers the north side of the island of Bali. Buleleng is the largest province of Bali in terms of area. During the colonial period, Singaraja was the capital of Bali and the Lesser Sunda Islands; in 1953 the capital was moved to Denpasar in the south. During the colonial period, the harbor in Singaraja was the entry point to the island for visitors and a variety of goods including slaves and opium.

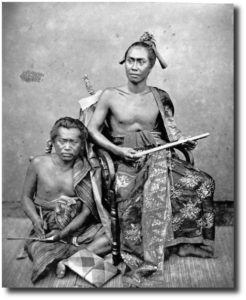

Raja of Buleleng and his secretary circa 1875. Image:

Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute

Buleleng was founded on March 30, 1604, by the legendary Gusti Panji Sakti who was descended from the son of Dalem Sagening, king of Gelgel, and who at one time ruled both Buleleng and Blambangan in Java. The story goes that Panji Sakti left Klungkung to found a new kingdom in North Bali. When Panji Sakti reached the top of the mountain range, he was thirsty, but there was no water. So, he drove his magic kris into the ground and a spring formed. This spring still exists today at the site of the Pura Yeh Ketipat temple in the Lake Beratan area. Eventually Panji Sakti built three palaces; the last palace was at the site of Singaraja and this is considered the official birth date (1604) of the city and the kingdom of Buleleng.

Buleleng was the first of the Balinese kingdoms to fall to the Dutch after three battles in 1846, 1848 and 1849. (I’ll have more about this in my posts about the Bugis in Kampung Bugis.) Buleleng has 9 kecamatans (sub-districts); these are Gerokgak, Seririt, Busung Biu, Banjar, Buleleng, Sukasada, Sawan, Kubutambahan and Tejakula. Geographically Buleleng includes mountain ranges in the south, two lakes in the mountains and the relatively narrow coastal plane that skirts the Bali Sea on the north. Agriculture, manufacturing, tourism and crafts are the main areas of the economy. The regency’s land area is 24.25% of the total land area of Bali. Buleleng’s has a varied climate; the mountain ranges to the south regularly receive rainfall, while the coastal area has a dry season and a wet season.

According to the Kabupaten Buleleng’s website, the regency (or district as it is sometimes called) had a population of 786,972 in 2009. While the sub-district of Buleleng has the smallest area of the nine sub-districts, it has the largest population and highest population density. The sub-district of Buleleng had a population of 146,942 with a density of 1,515 people per square kilometer; the city of Singaraja has somewhere between 80,000 to 100,000 residents and this accounts for the high population density of Buleleng. Singaraja is known as a city of education.

Kampung Bugis is located right along the Bali Sea (sometimes also called the Java Sea or the Bali/Java Sea), and is adjacent to the harbor. The total area of Kampung Bugis is 30 hectares. In addition to having the sea as its northern border, it borders Kampung Baru to the east, Kampung Kajanan to the south and Kampung Anyar to the west. The kampung has 3,299 residents, divided almost equally between males and females. Trading is the most common occupation, and there are 21 residents listed as making their livelihood by fishing.

A few posts ago, I mentioned that I was going to get some needed exercise while exploring the city that I’ve called home for most of the past 23 years. I’ve been waiting to get over a bout of pneumonia, but it’s been a long time coming – getting well that is – so I’ve decided that the best way to speed my recovery at this point is to just get out and do some walking. One thing that I’ve discovered while planning my walking tour of the city on a map is just how big Singaraja actually is. That little discovery has surprised me, I think, just because I’ve taken the city for granted. It’s a fairly common thing for people to fall into comfortable routines, and we miss all of the wonder and the changes around us. So, if I really want to do right by Singaraja, I’m going to be doing a lot of walking over the coming months.

I’ve been thinking about how best to do my little walking tour, and I finally decided that the best place to start is from home. It makes a lot of sense geographically because we are right at the edge of the world – so to speak – because three meters in front of our house is the Bali Sea and that’s where Singaraja ends. So, I’m starting out from home and making little forays farther and farther out from the house.

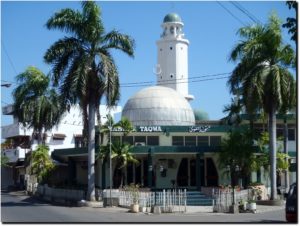

My first walk is just a little stroll out of Kampung Bugis past Masjid Taqwa down Jalan Diponegoro (Singaraja’s central business district – that’s probably too grand a title for Jalan Diponegoro, but I like it so why not) then over to Jalan A. Yani and back down Jalan Imam Bonjol to the harbor and home again. The route is traced out on the map of Singaraja for readers who want to locate the areas that I’m writing about on a map. Jalan Diponegoro is the central shopping area and the city’s main traditional market is located right in the middle of the street although it can be a bit difficult to discover because the entrance is just a small opening on Jalan Diponegoro – the actual market is between Diponegoro and Jalan Imam Bonjol. The market has fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, spices, clothes and a variety of other dry goods. Really, I don’t find it all that interesting, although it does seem to attract a number of tourists who want to see a traditional market.

The street also has electronic stores (I buy all my electronic equipment there), a few small restaurants, shoe stores, a few book stores (including a new one that I just discovered on this walk), a pharmacy, a few doctor’s offices, some fishing equipment shops, a small mini-market, two or three clothing stores, the main branch of BII (Bank Internasional Indonesia), a few hair saloons, a few gold shops, and an assortment of shops selling household goods. The street is almost always crowded with traffic due to the relatively new practice of allowing double parking which causes traffic to back up during the busy shopping hours of the day. I’ll get back to discussing Jalan A. Yani in another post.

Jalan Imam Bonjol is another busy street just to the east of Jalan Diponegoro. It is filled with shops selling a variety of things, such as household goods, furniture, car and motorbike parts, gold jewelry, and children’s toys. This street also has an entrance to the main market and a new mini-market. While Jalan Diponegoro is a one way street running north, Jalan Imam Bonjol is a one-way street running south. Most of the buildings are two stories with a shop on the ground floor and a residence on the second story. Running off of Jalan Imam Bonjol to the east and west are several small streets called gangs in Bahasa Indonesia.

|

| A map of my walks. |

After leaving Kampung Bugis walking to the east comes the intersection of Jalan Diponegoro and Jalan Erlangga. Actually, Jalan Dipongegoro becomes Jalan Erlangga in that way that streets do here. Navigating any city in Bali is made more difficult by the fact that house and shop numbers do not necessarily change sequentially and one street suddenly becomes another without warning. Detailed maps may be of some help, but how many of us carry maps around with us? So out onto Jalan Erlangga; this is a short street. This part of it is narrow and often congested because of traffic coming from Jalan Diponegoro, which, as one of the main streets of Singaraja, gets a lot of traffic, and Jalan Pattimura which runs through Kampung Bugis and gets a lot of traffic because all of the trucks coming from the west have to be routed through Jalan Pattimura. Find a photo. A lot of cars and delivery trucks double park here which adds to the congestion.

Jalan Erlangga has a large furniture shop where we buy most of our furniture. We’ll occasionally run into foreigners from the Lovina area shopping for furniture there. This is not the expensive custom made furniture, but they have some nice beds and a few other pieces. One the south side of Erlangga is another furniture shop. We buy things there occasionally. Additionally, there are several automotive parts stores, a fishing/photography shop, a small grocery store selling dry goods and beverages, a baby shop and at several bicycle stores. Other buildings include a mosque and a store selling generators, hardware and other building tools.

|

| Jalan Hasanuddin, Singarja Bali |

Jalan Erlangga continues on past the intersection with Jalan Imam Bonjol. Here, Jalan Erlangga becomes a wider two-way street. Both sides have a number of shops selling building supplies such as paint, plywood, ceramic tiles, tools, varnish, nails and bolts, cement, and a variety of other building materials. This section of Jalan Erlangga continues on about 200 meters until it reaches the entrance to the old harbor and the bridge; it then becomes Jalan Surapati. Right across from the entrance to the bridge on the south side of the street is the start of Jalan Hasanuddin. Like Jalan Imam Bonjol, Jalan Hasanuddin is a one-way street running south. A lot of the buildings on Jalan Hasanuddin are storage facilities for local businesses. There is a busy pharmacy, a dentist’s office and a pediatrician’s office close by. Going south a ways is a pet supply store. No pets, just supplies like cages, aquariums, food for any number of creatures, and cigarettes. Yes, this pet store sell cigarettes.

Jalan Hasanuddin continues on south until it curves to the west and joins up with Jalan Imam Bonjol. As I walked this short stretch, I could hear the screams and laughter of children. I looked up and noticed an elementary school. I expected that because of the noise level the kids would be out on recess, but they were safely tucked away inside the classrooms. A large bathroom and tile store sits right at the intersection of Hasanuddin and Imam Bonjol. We’ve bought a few faucets and a toilet from them. They have a small, but interesting selection of bathroom fixtures, including a large solar water heater. This kind of store wasn’t around in Singaraja when we were building each of our houses. To get Western-type building supplies, we had to go down to Denpasar, and even there, the selection was limited. Singaraja has become more Western friendly in terms of construction materials, and, even Indonesians are now buying Western-type furnishings for their homes. Recently we visited a neighbor’s house and were surprised to see that they had a Western toilet in their bathroom along with a fancy sink and cabinet set. Across the street is a fairly large building supply store that sells paint, wood, plastic piping and so on.

And just where Jalan Imam Bonjol ends and splits into two streets, Jalan Gajah Mada starts and leads south to Denpasar. Jalan Dr. Sutomo splits off to the west for a short distance and becomes Jalan A. Yani which heads off to Lovina. Right at this busy intersection (noticeable for the large statute that marks the intersection), Singaraja’s post office is located. Generally the post office isn’t too busy, and it now has a small ATM in the parking lot.

I follow Jalan Dr. Sutomo – it only runs about 150 meters at the most – over to Jalan Diponegoro. Jalan Dr. Sutomo has a mix of small businesses that sell books, household goods and electronics. There is also a small internet shop that I used a few times when my internet connection was out. Perhaps most importantly, Bank Central Asia is here just across from the south entrance to Singaraja’s main market. BCA has an ATM machine and inside it’s possible to change currency including traveler checks. A police post, a clothing store and a motorcyle store are also located here.