This is the continuation of a series of posts on Papua New Guinea. For the most part, these posts will be on the ethnic groups (or tribes as they are often called) that I visited over the approximately three months that I traveled through coastal and island PNG villages during the period of 2017-2018. Some of what I write here is based on observations and discussions that I had with local people; some is based on the many ethnographies written by anthropologists about these same people.

These posts are basically snapshots of a handful of the fascinating cultures of Papua New Guinea. I’m starting with the Murik culture because it was my first stop on my most recent trip. Second post will be a small introduction to the Sepik region.

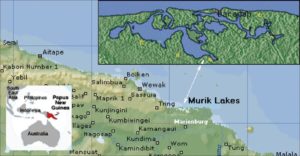

This post is on the people of the Murik Lakes area at the mouth of the Sepik. I visited one of the five main village three times in February and March of 2018: Mendam is a small village of 400-500 people. In addition to my observations, I’ve relied heavily on the work of the anthropologist, David Lipset, who has done extensive fieldwork in the Murik region.

The Murik Lake People

The Murik people live along the north coast just off the mouth of the Sepik in the Sepik estuary. They live in five main villages in an area of mangrove lakes, swamps and sandy beaches. This area makes up the largest mangrove ecology in PNG.

They live in five main villages in an area of mangrove lakes, swamps and sandy beaches. This area makes up the largest mangrove ecology in PNG.

The Murik, according to legend, migrated to the area from around the town of Angoram around 400 years ago. They have had extensive contact with Austronesian-speaking people along the coast and nearby islands, as well as with non-Austronesian groups living up along the Sepik River.

The population is around 3,500 in five traditional villages, although population statistics are fairly flexible in PNG. An example: in one village that I visited in another area of the Sepik four times over a one-month period, I was told that the population was 3,000, then 4,000 and finally 5,000. So, unless these folks were reproducing rapidly, the numbers are not set in stone.

In addition to their traditional home land, some Murik live in the town of Wewak where they seek a cash income. The Murik presence in Wewak, the capital of the East Sepik Province, has been ongoing for decades. The Murik tend to live in rather rough squatter camps in Wewak, similar to people from the Chambri Lakes region of the Sepik.

History

The Murik people have long been in contact with the coastal Austronesian groups that settled in this area some 2,500 years ago. Trade relations led to cultural exchanges as well, as can be seen in some of the Murik dances, carvings, and marriage patterns.

marriage patterns.

First contact with foreigners was in 1616 with the Dutch captain Jacob Le Maire.

Because of the poor quality of the land, the Murik were basically left alone by colonists. However, a German Catholic mission was established around 1913. Some German troops under a rogue commander burned men’s houses and destroyed sacred objects during this period, not exactly endearing them with the Murik people.

During the Australian period between WWI and WWII, some Murik began to leave the villages for work. This generally consisted of domestic type work for the missions. The Japanese arrived in 1944 and spent a year in the Murik Lakes region.

After the war, some Murik began to seek Western-style education and employment. Papua New Guinea’s first PM was Michael Somare from the Murik village of Karau.

Residences, Village Life, Architecture

Similar to most houses in the Sepik River region, houses here are built on stilts from just a few feet above ground level to as much as about 8 feet above the ground.  While at one time the ideal was to have houses arranged by descent groups, that pattern is less likely to be followed these days because of the frequent flooding of the land. Extended families usually live together until it gets too crowded

While at one time the ideal was to have houses arranged by descent groups, that pattern is less likely to be followed these days because of the frequent flooding of the land. Extended families usually live together until it gets too crowded

Like all groups along the Sepik, the Murik have men’s cult houses, although not every village has one. While I was visiting Mendam, I asked where the haus tambaran (the spirit house) was and was told that the village didn’t have one. Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to get more details on why there wasn’t a spirit house in the village. While it’s possible that the house just wasn’t open for tourist viewing, that seems unlikely as one of the major points of interest for tourist groups is visiting the spirit houses where they have a chance to learn some local history, hear a little traditional music and sometimes by some artifacts. So, that’s something that I hope to learn on another trip to Mendam village.

Economy

Because of the geography, subsistence activities center on fishing and trade, with a little hunting. The staple is sago, which is generally traded for because of the scarcity of sago palms. In addition to sago, the other common foods are fish and shellfish that are abundant in the area. The villages also have coconut groves that can be harvested.

There is little arable land in most of the villages so the Murik don’t have much garden produce. During the dry season when the waters retreat, a few small gardens can be rapidly planted, but for the most part, the Murik are dependent on trade for vegetables. Manufactured items such as pots and plates are sought in exchange for baskets.

Because a cash economy has beco me so pervasive in PNG and lacking land to grow cash-crops and trees to sell to the foreign concessions, the Murik are dependent on the occasional sales of carvings and baskets, as well as remittances from family members who have moved to the cities to engage in paid labor. I was told in Mendam (as I was in all of the villages that I visited) that they welcomed tourism because it provided a cash income and encouraged the younger members of the community to keep up with the traditional culture.

me so pervasive in PNG and lacking land to grow cash-crops and trees to sell to the foreign concessions, the Murik are dependent on the occasional sales of carvings and baskets, as well as remittances from family members who have moved to the cities to engage in paid labor. I was told in Mendam (as I was in all of the villages that I visited) that they welcomed tourism because it provided a cash income and encouraged the younger members of the community to keep up with the traditional culture.

In addition to food and some manufactured items, important trade items include magic, songs and dances, and designs for artwork.

Sociopolitical organization

Leadership in Murik villages generally goes to the senior men of the various descent groups. This usually means the first born, as primogeniture is the rule for the Murik. When there are disputes within the village, they are discussed in the men’s house with the senior men having the most say. If this fails, then there are village courts that can adjudicate the problems at hand.

While in the past warfare was a common solution to solving conflicts between groups, including problems between Murik villages, these days a serious attempt is made to talk things out. Still violence is an option at times. Sexual jealousy is a common cause of conflict within and between villages.

Marriage, Family, Kinship

Marriage tends to be somewhat unstable until children come along. No special rituals or rules for marriage other than obtaining the consent of parents and following the rules of exogamy. Where once they may have practiced brother-sister exchange, which is a preferred form of marriage where one family o

r group will exchange a woman (someone’s sister), now they do not bother with that. The Murik do not practice bride wealth but do have bride service, which is where a man works for a period of time for his father-in-law.

Couples can choose where to live. In the case of divorce, they may return to their parents’ houses. Children are encouraged to be independent; the eldest are expected to care for the younger ones. And just as in the culture where I live, elder sibs tend to have fun teasing their younger siblings, at least until the parents hear the fuss that this causes.

According to Lipset, “Unlike the highlands peoples with a culture that tends to be highly misogynistic, the Murik, partly due to their geographical location, have a culture where gender is not highly stratified, but rather where men and women are interdependent and work together in a mode more like the Austronesian cultures of the offshore islands, while remaining well within the Sepik tradition.”

Magic and Religion

Christianity came to the village of Big Murik in 1911 with the Catholics. In 1951, the Seventh Day Adventists set up a mission in Darapap Village. So, while Christianity has a long history here, the traditional beliefs are still practiced. This co-existence of Christianity and traditional religion is commonly found throughout Papua New Guinea.

Magic is alive and well (and sometimes not so well) in Papua New Guinea. From villagers to urban dwellers, magic still has a strong place in the peoples’ world views. The Murik believe in many spirits that can, like human beings, be good or bad, cause illness, death and misfortune or help control the weather, make the crops grows, regulate social life, heal the sick and attract a mate. Ancestor spirits play a key role in the Murik belief system, but there are also animistic spirits that need to be addressed in daily living.

Murik stories about their identity are about ancestor-spirits who, unlike the ancestors of other groups, are not superhuman or gods, but rather ancestor-spirit men and women who are superior to regular men and women only in degree. They do not possess divine powers, but resolve conflicts and problems through essentially human means, but their spirit world is inhabited by talking animals, ogres and similar creatures. Origin legends revolve around a pair of spirit-men who are brothers.

Art and Music

Men are carvers; women weave baskets. The women’s baskets are distinctive and rarely found in other cultures along the Sepik. As with many of the et hnic groups in the Sepik River area, the Murik have a distinctive style of carving. Masks tend to display a stylized oblong form. A carving school for youths to keep the art alive and for people who felt there was nothing in the modern world for them was started by a well-known former politician who owns a large resort in Madang and who is frequently on the Sepik River with his luxury yacht filled with tourists who want to experience the cultures of the Sepik River.

hnic groups in the Sepik River area, the Murik have a distinctive style of carving. Masks tend to display a stylized oblong form. A carving school for youths to keep the art alive and for people who felt there was nothing in the modern world for them was started by a well-known former politician who owns a large resort in Madang and who is frequently on the Sepik River with his luxury yacht filled with tourists who want to experience the cultures of the Sepik River.

The Murik people have their own style of dance and drama. They are especially proud of their short humorous plays that they perform for visiting tourists. The actors are all male and a common theme is a misunderstanding during a traditional activity, often an initiation ritual.

Modernity

As with other groups, a need for cash income leads some people away from home- temporarily or permanently.

Climate change poses another challenge. Due to their geographical location, the Murik have experience intense flooding from tidal changes. Several villages have been completely washed out in the recent past.  The Murik Lakes Resettlement Project (MLRP) was started in 2003 but failed. Local initiatives followed, and a new village was built after the 2011 tsunami. Temporary solutions have yet to lead to permanent ones. This is the challenge for the Murik and other coastal dwelling people today.

The Murik Lakes Resettlement Project (MLRP) was started in 2003 but failed. Local initiatives followed, and a new village was built after the 2011 tsunami. Temporary solutions have yet to lead to permanent ones. This is the challenge for the Murik and other coastal dwelling people today.

Increased access to education offers the hope of employment outside the village. For villagers who move into the modern economy, there can be a disconnect with “traditional” culture. Bridging the gap is a challenge for the new generation